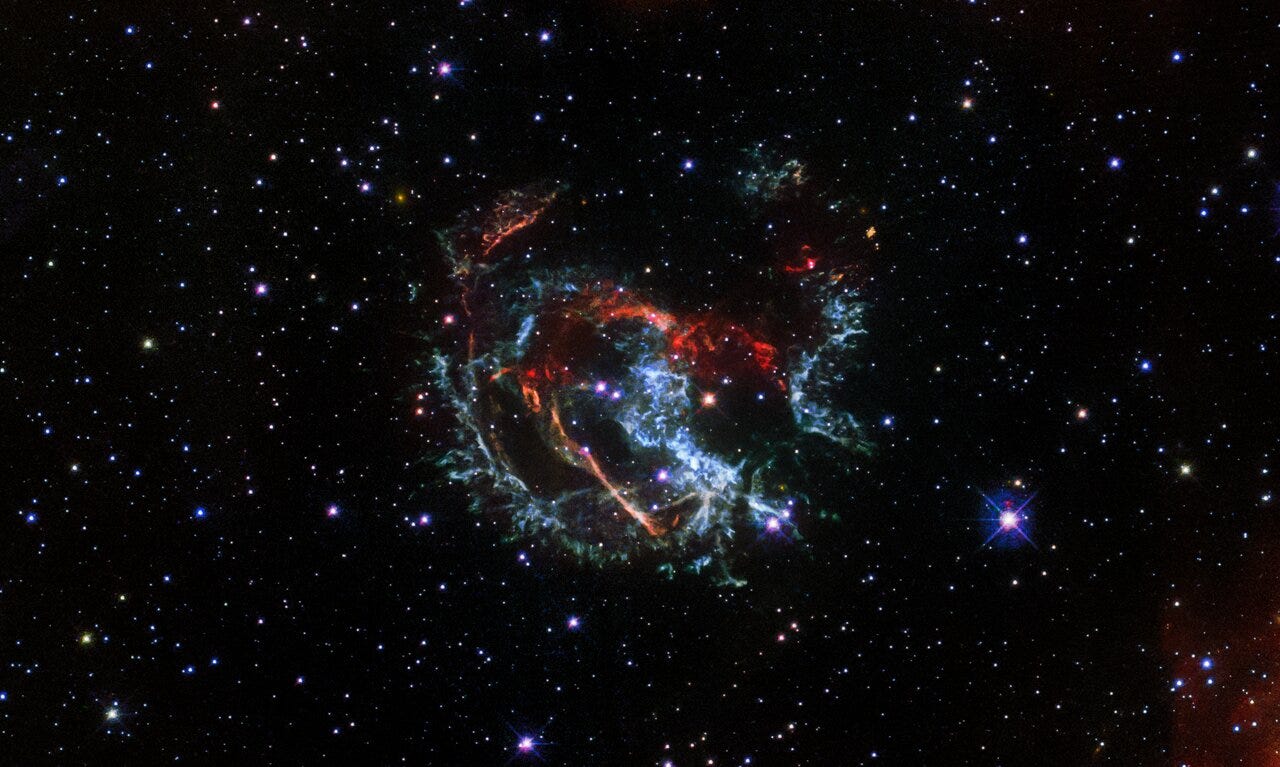

Unfortunately, no records survived telling of this celestial event south of the equator. However, astronomers have now turned the mighty gaze of the Hubble Space Telescope to examine the remnants of this titanic explosion, called 1E 0102.2–729. By studying the cloud of gas and dust left behind, astronomers hope to piece together the story of the eruption that created this magnificent nebula.

1E 0102.2–7219 — Charming name. Rolls off the tongue…

The eruption forming the nebula was seen on Earth 1,700 years ago, but the explosion was not recognized by astronomers until recently. Seen in the Small Magellanic Cloud (a satellite galaxy of our Milky Way 200,000 light years from Earth), this nebula was first seen, in X-ray light, by NASA’s Einstein Observatory. By studying images of 1E 0102.2–7219 taken by the Hubble Space Telescope 10 years apart, astronomers were able to see how the nebula changed over time. Knots within the nebula move at different speeds and directions from the center of the blast, at average velocities of 3.2 million kph (almost two million MPH). At that speed, it would be possible to travel from the Earth to the Moon and back in just 15 minutes. [Read: How Netflix shapes mainstream culture, explained by data] Earlier studies of 1E 0102.2–7219 concluded the blast was seen on Earth between 2000 and 1000 years before our time. But, this new study examined the 22 fastest knots within the nebula, finding the nebula formed 1,700 years before our time.

Please be kind and rewind

Tracing back the paths of these tadpole-shaped, oxygen-rich, clumps of material in the nebula allowed astronomers to close in on this new age estimate. Ionized oxygen is often used as a tracer since it glows most brightly in visible light. “The suspected neutron star was identified in observations with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, in combination with data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory,” The Hubble Team reports. The neutron star (likely) left behind by the explosion was also seen racing away from the center of the blast at more than three million KPH (1.86 million MPH). “That is pretty fast and at the extreme end of how fast we think a neutron star can be moving, even if it got a kick from the supernova explosion. More recent investigations call into question whether the object is actually the surviving neutron star of the supernova explosion… Our study doesn’t solve the mystery, but it gives an estimate of the velocity for the candidate neutron star,” John Banovetz of Purdue University stated. Researchers found many knots within the nebula had previously slammed into the material ejected from the star prior to the explosion. These collisions slowed down some clumps, affecting earlier observations. “A prior study compared images taken years apart with two different cameras on Hubble, the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 and the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS). But our study compares data taken with the same camera, the ACS, making the comparison much more robust; the knots were much easier to track using the same instrument. It’s a testament to the longevity of Hubble that we could do such a clean comparison of images taken 10 years apart,” Danny Milisavljevic of Purdue University explains. Around the year 320, the Roman Empire was crumbling, and science was rejected by a large percentage of the population. Border skirmishes, political assassinations, civil wars, and barbarian attacks ate away at the once-mighty empire. It may be a good thing people in the Northern Hemisphere could not see the “new star.” Who knows how such an “omen” would have affected history? Astronomy News with The Cosmic Companion is also available as a weekly podcast, carried on all major podcast providers. Tune in every Tuesday for updates on the latest astronomy news, and interviews with astronomers and other researchers working to uncover the nature of the Universe.