This has attracted numerous mining companies, with their focus especially on one lake in northeastern Chile called Salar de Atacama. This is estimated to contain almost 30% of the globe’s known lithium. But as promising as this sounds for our beloved EV batteries, it comes with a high cost: the area’s biodiversity. A new study suggests that mining operations around the lake are linked with the decline of two threatened flamingo species residing in the basin.

Lithium mining is thirsty work

The Andean Highlands might be amongst the Earth’s driest places, but it contains numerous large saline lakes, such as Salar de Atacama. Thanks to these, the area is rich in salty groundwater, called brine, where lithium can be found. The thing is, producing a single ton of lithium requires roughly 400,000 liters of water, according to the study. That’s because mining companies pump and evaporate the liquid in order to extract lithium. Alarmingly, this process shrinks nearby lakes where flamingos eat and breed. In Salar de Atacama, for instance, it’s estimated that more than 1,700 liters of lithium-rich brine is pumped from the ground every second. As the lakes retreat, they become saltier, which can affect or even kill the aquatic organisms flamingos eat. And, without enough food, the birds reproduce less, fly elsewhere, or starve.

Doing the fandango for flamingos

The researchers found that flamingo populations in Salar de Atacama declined 10-12% between 2002 and 2013 (the most recent years with reliable data). The team links the decline with the increase of lithium mining over those years, as an 11% drop in the lake’s water surface was observed during the winter months. It’s also possible that “noise and vehicle traffic” from mining operations negatively affect the birds, the authors add.

Why we need to protect nature

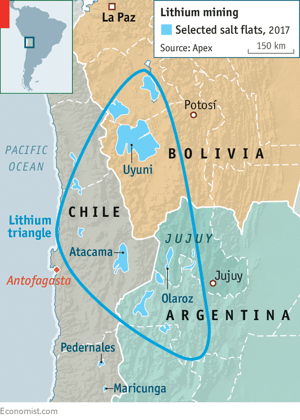

Flamingos aren’t just beautiful to look at — and my favorite bird for that matter. They’re actually vital in brine lake ecosystems and for Salar de Atacama in particular. As per the study, flamingos are grazers, spending much of their time chewing tiny organisms from the bottom of the food chain, which contributes to the ecosystem’s balance. They’re also a barometer of lake health, meaning that if they can’t survive, no other avian species can either. On top of that, many local communities in the region depend on those birds for tourism. But there’s some good news too: flamingo populations haven’t declined across the broader Lithium Triangle region. This means that while mining in Lake Atacama threatens the birds, other lakes can still support them, and even buffer losses elsewhere — showing that mining operations should at least limit their geographical expansion and impact. It’s no secret that the boom for lithium demand has been having a negative impact on wildlife and biodiversity. And instead of mitigating losses, the industry should focus on more sustainable mining practices, or — better yet — on lithium recycling. If we need the material, the least we can do is ensure it’s obtained in the safest and greenest way possible.